This blog provides a clear distinction on these terms often used interchangeably.

Execution Image

An execution image generated after compiling, assembling, and linking a C program has the following sections:

- Text (or Code) Section ( .text): This section contains the machine code for the executable instructions generated from the C source code. It includes the actual executable code for functions and instructions that the CPU will execute.

- Data Section ( .data): This section contains initialised global and static variables defined in the C code. It reserves memory for these variables and initialises them with predefined values. For example, int x = 10; would be stored in the .data section.

- BSS (Block Started by Symbol) Section ( .bss): This section contains uninitialised global and static variables. These variables will be initialised to 0 on runtime.

These sections are statically allocated—that is, after creating the image, the addresses for the objects contained in the text, data, and bss sections are already defined.

Stack and Heap

Stack and Heap are memory usage models – we also happen to name memory regions after their usage models.

The stack is where data is accommodated as the process executes. It is defined as starting at the highest address, often with a maximum pre-established size. It is commonly said that the stack ‘grows downwards’ because of its push-pop (Last-In-First-Out) usage model.

The remaining main memory space—between the .bss and the stack bottom—is commonly left to be used as the Heap, from which memory chunks are taken and given back at runtime, and differently from the stack, it grows upwards. The allocation/deallocation discipline can vary: first-fit, best-fit, and fixed-size, to name a few. Depending on the system requirements, an explicit heap region can or cannot be present.

Together, these components form the runtime memory layout, sometimes called the runtime image, as depicted in the picture, with the specific .isr_vector symbol for the ARMv6/7M vector table. (Just so you know: formally, an execution image does not include stack and heap).

This memory layout represents a crucial part of the runtime environment, including the program’s code, linked libraries, and interaction points with the overall system. In fact, if there is no dynamic linking, this is the runtime environment per se.

Now, we need to distinguish between Processes and Threads clearly. The latter is the fundamental Concurrency Unit in RK0.

The Process Model

An image is a static entity; as a matter of fact, an image is a program. A process is formally defined as the execution of an image. This definition is used in the seminal UNIX paper and is still valid but not enough for the modern process concept. A process is better described as a container in which code is executed along with the usage of machine resources (I/O, storage memory, main memory, and so forth), all within the boundaries of a memory space. In general-purpose operating systems, each process has its own virtual address space, a mechanism provided by a specialised hardware, the Memory Management Unit (MMU). A process is a schedulable entity, and an operating system enables multiprogramming by switching between processes.

As you can see, the modern process concept is about program execution as much as isolation. However, when the idea of process was first coined, the isolation level between application programs was much less, making it essentially what today we refer to as a thread, an abstraction solely related to program execution.

The Thread Model

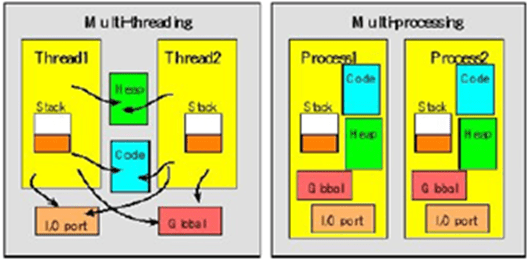

A thread is a logical sequence of instructions that executes code. Thus, a process is an executing program consisting of one or more threads within an address space. Each thread has its execution stack and, at any given time, its execution context. The execution context is the set of values on the core registers when a task is active. If we want to pause a thread to be resumed later, the execution context at the moment must be saved somewhere in memory. Threads within the same process have no boundaries – they are all in the same address space. This lack of isolation makes them highly coupled execution units. Like processes, threads are also schedulable entities. Multiple threads within a process enable a second level of multitasking in a multiprocess environment.

This second level of concurrency yields benefits for user applications on general-purpose operating systems, as they can benefit from concurrency with a lower overhead than on the process level: it is faster to switch between threads. This lighter concurrency led threads to be regarded as lightweight processes (LWP).

(On low-end devices, isolating threads using Memory Protection Units is possible. Still, they all see the same physical address space. This isolation works more like a memory firewall.)

Task has no model

While Processes and Threads are relatively well-defined models, a Task is a loose concept. In the Linux kernel, a Task is the schedulable entity, and from the scheduler’s point of view, there are only Tasks. A Process is a Thread Group: in a group, tasks share resources. There are no distinct abstractions for a Process or a Thread; there are only Tasks (a Thread Info structure is allocated on each execution stack).

In Windows (NT kernel), a process is a container of threads. Unlike Linux, these are different abstractions, and threads are indeed the only schedulable entities, as processes are not scheduled in the strict sense (even if a process has a single thread). There is no ‘Task’ thing.

In macOS (XNU kernel), a combination of Mach and BSD kernel concepts is employed. BSD processes are identified by PIDs that are paired with Mach Tasks identified by Ports. Tasks are containers of threads, which are the schedulable entities. It deserves a drawing:

+-----------------------------------+

| BSD Process (PID) |

| +-----------------------------+ |

| | Mach Task (Port) | |

| | | ~ Thread | Thread ~| | |

| +-----------------------------+ |

+-----------------------------------+

In general, on today’s operating systems (including all those mentioned above), the thread is the schedulable unit, and the prevailing model is that 1 user thread maps to 1 kernel thread. In the early days, a kernel would see only a user process, not being accountable for scheduling threads – a blocked system call would cause switching processes. (UNIX Solaris was notable for having kernel threads as a schedulable unit, in the beginning mapping N user threads to M kernel threads (N>M) and eventually settling to 1:1 )

(…. enough ….)

What it all means

Multiprogramming involves multiple processes (hence multitasking at the process level), multitasking can occur within a single process without implying multiprogramming. Typically, in system software for constrained embedded devices, multitasking occurs over a single execution image, i.e., within a single process or program.

In RK0, a Task is a Thread, the logical unit of concurrency. The final takeaway is that while a process gives the illusion of a dedicated entire machine (CPU, memory, and I/O), a thread is a dedicated CPU. Everything else is shared. This lack of isolation has drawbacks and benefits – the ability to communicate over shared memory benefits performance and predictability. But, as threads can easily interfere with each other, the design must be conservative, and the programmer cannot afford the luxury of not knowing the hardware. Reasoning about multithreading behaviour is difficult; a lean, structured embedded kernel makes it easier.

/* comment here */