So far, we have discussed tasks coordinated by Signals. Signals do not convey data in the strict sense—the meaning of the communication is implicit.

MESSAGE PASSING

The read value on a sensor, a checksum, a command with its payload—all of these are examples of Messages. Message Passing provides the mechanisms to exchange data and also to synchronise (after all, if Task A sends a message to Task B, B can only receive the message at some point in time after A has sent it).

Shared Memory and Message Queues

Processes are isolated on more high-end embedded devices and on General Purpose Operating Systems that utilise Virtual Memory (at the lower end, we still can achieve some isolation using Memory Protection Units). Message Queues are a mechanism to circumvent this isolation by asking the kernel to convey data from one address space to another. For these systems, Shared Memory, when applied, is a pre-defined memory area, which processes will attach to so they can write and read from – without relying on the kernel.

(a) Message Passing (b) Shared Memory (Silberschatz)On embedded operating systems for constrained embedded devices, often all tasks share the same address space (therefore, every memory is shared memory). In this context, message passing provides a way for tasks to exchange messages in a controlled manner.

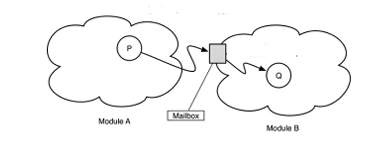

A Message Queue (generally, a Mailbox) is a public structure for message passing. They are often constructed as circular buffers or linked lists of buffers. The queue discipline is typically FIFO, but LIFO and message priority are possibilities.

Fig 2. Two modules communication through a mailbox (Bertolotti)A communication link or a channel is said to exist between producers and consumers. At the very least the channel will support two primitives: send and receive. This link has the following properties:

(a) Buffering

Buffering is about how many messages can wait on the channel. If we decide that no message can ever be waiting, logically, we have zero buffering: a successful transmission is a successful reception. For a bounded buffer, we have one or more messages that can be stored; successful sending does not mean successful receiving – it means the message has been deposited, not it has been extracted.

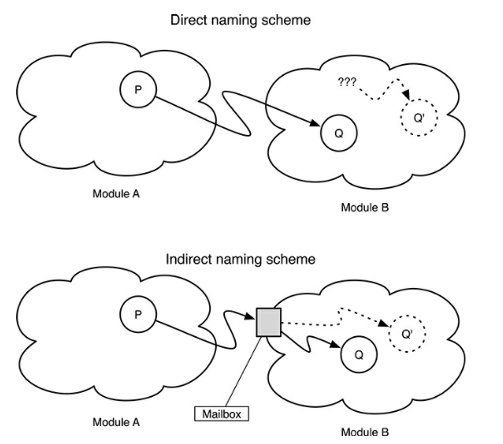

(b) Naming

Naming can be direct or indirect. Indirect naming means the communicating tasks will use the channel’s name to send to and receive from. On a direct channel, the send() gets a task ID as argument.

When a receiver does not need to name a sender task or a mailbox, the naming scheme is said to be asymmetric – otherwise, it is symmetric – as a send() always needs a destination point – a task or an object.

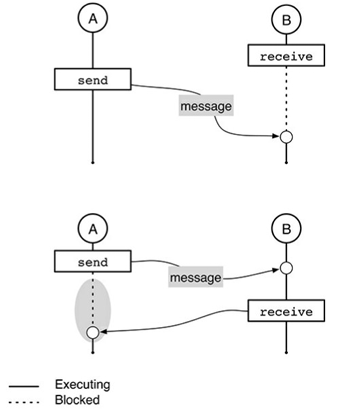

Fig 3. Naming schemes(c) Blocking or non-blocking

For blocking operations, a producer blocks on a full buffer, and a consumer blocks on an empty buffer.

Non-blocking operations will always return, whether successful or not.

Fig 4. On top, a consumer sleeps waiting for a message. Below, a producer sleeps waiting for a successful send.Unbuffered Message-Passing

When the channel is logically unbuffered the sender will remain blocked until it receives an acknowledgement indicating that the message was received: the send operation was successful, and the consumer got the message (note that on Fig. 4. the sender is sleeping until the message is sent. A clear unbuffered communication would also depict message/signal from B to A.)

This pattern is inherent to a synchronous command-response – the sender blocks waiting for a message conveying the result of its request. If no response is expected, the acknowledgement can be a dummy message or a signal.

It can be applied in cases where the communication link is unreliable and/or the message is too important to be lost or whenever we need tasks to run in lockstep.

MESSAGE-PASSING ON RK0

RK0 provides a comprehensive set of message-passing mechanisms. The choice of these mechanisms took into account the common scenarios to handle:

- Some messages are consumed by tasks that can’t do anything before processing information — thus, these messages end up also being signals. For Example, a server needs (so it blocks) for a command to process and/or a client that blocks for an answer.

- A particular case of the above scenario is fully synchronous: client and server run on lockstep

- Two tasks with different rates need to communicate, and cannot lockstep. A faster producer might use a buffer to accommodate a relatively small burst of generated data, or a quicker consumer will drop repeated received data.

- Other times, we need to correlate data with time for processing, so using a queue gives us the idea of data motion. Eg., when calculating the mean value of a transductor on a given period.

- For real-time tasks such as servo-control loops, past data is useless. Consumers need the most recent data for processing. For example, a drive-by-wire system, or a robot deviating from obstacles. In these cases the message-passing must be lock-free while guaranteeing data integrity.

All Message-Passing mechanisms in RK0 can be classified as indirect (messages are always passed to a kernel object) and symmetric (both sender and receiver need to identify the object). They can assume buffer or unbuffered, and also blocking or non-blocking behaviour.

The RK0 Docbook contains implementation details, special operations, usage cases, and patterns for these mechanisms.

/* comment here */